|

The absurdity of such arguments is easy to illustrate. We need only remember that, between 1 April and 5 June 1944, the Allied air forces mounted 195,255 sorties in support of Overlord, dropping 195,380 tons of bombs, losing 1,987 aircraft and destroying 2,655 enemy aircraft in combat. Yet this is not merely a reflection of the weight of the Allied air effort. It also illustrates the Allied calculation that air power could and should support the landings over an extended period, before the troops went ashore, in a broad range of pre-planned operations that achieved cumulative effects during the build-up to D-Day.

Fundamentally, this was a scientific approach to air-to-ground targeting for Overlord, and it was based on an operational perspective of the battlespace. It involved the identification of target systems or networks, the destruction of which would achieve operational effect, the importance of which could be measured against other target networks. Each network was then subdivided between identified targets, which became intelligence (overwhelmingly air reconnaissance) objectives, and intelligence allowed the relative importance of individual targets within the network to be established; it also provided a basis for mission planning, including the scale of effort likely to achieve the desired outcome, and weapon-to-target matching.

After each attack, air reconnaissance and any other available intelligence would provide Battle Damage Assessment (BDA) confirming the destruction of the target or the need for re-attack. Through this procedure, the Allied air forces progressed systematically through the various target networks; targeting was directly linked to the achievement of an operational effect - successful Allied landings in Normandy.

|

| An RAF Typhoon strike on a Luftwaffe Ju 88 during the build-up to D-Day. |

|

| Typhoon rockets launched against a German radar station; radar and associated sites were another key target network for the Allies before the landings. |

CAS is very different. Moreover, it is widely misrepresented, even by air power historians. It does not merely involve the provision of direct air support to ground troops. The defining characteristics of CAS are: detailed integration of air and ground forces, and the presence of a terminal controller, normally on the ground, communicating with the attacking aircraft. These features reflect the necessity of accurate target identification and ‘deconfliction’. CAS is normally conducted against targets near to friendly forces; therefore, measures to prevent fratricide and enable the attacking pilot to distinguish between friendly and hostile forces are essential.

This procedure was still very unusual in June 1944. It was more common for forward troops to pass requests for air support to higher C2 nodes capable of obtaining offensive air power, but this is not CAS. It might be described as direct support, and it was, after the war, termed Battlefield Air Interdiction, but the essential elements of detailed integration and terminal control were absent. It was also far less dynamic than CAS. Many of the requests were submitted by well established units at known locations, and there was often at least some prior knowledge of the target or target location too. We should not confuse this system with the Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) that would have been required to provide on-call air support to troops landing on the Normandy beaches, which would have had to be far more responsive and dynamic.

|

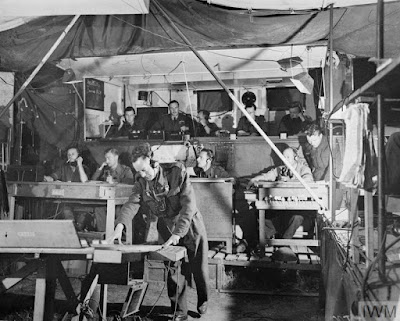

| Air Support Control signallers, pictured in the desert; their role was to pass air support requests back to higher C2 nodes. |

CAS is also much less scientific than pre-planned air targeting. It is largely employed against short-term emerging targets. Target selection is carried out by troops on the ground, usually in forward positions, who have an extremely limited view of the battlespace and of the relative importance of the task they are carrying out.

This process can easily become entirely divorced from the achievement of operational effect. This can happen when CAS is rationed out across ground formations on a 'fair shares' basis or used more to limit casualties than gain operational objectives. Yet in the Second World War this problem was well understood. It was fully recognised that prioritisation in the allocation of CAS was critically important if it was to be employed effectively.

In the campaign to liberate northwest Europe, using British forces as an example, this occurred at the Group/Army level - for example, Second Tactical Air Force’s 83 Group and Second (British) Army. The necessary command and control responsibilities could not be exercised without extensive deployed facilities, most of all communications. For high priority operations, Group could delegate tasking responsibility to forward C2 nodes that became known as Visual Control Posts or Forward Control Posts - later referred to as Forward Air Controllers. All available air support would then be assigned to the priority task in relays in what was referred to as a ‘cabrank’ to receive tasking from the forward controller. 83 Group and Second Army had plans to establish this system in Normandy after the landings, as the necessary C2 personnel and architecture deployed and the first air bases were constructed on French soil, but these were essential prerequisites. Such a system could not have been created before the Allies gained a foothold on the continent.

|

| 483 Group Control Centre in Normandy in 1944; the key to providing tactical air support lay in deploying the necessary C2 and communications. |

|

| A Visual Control Post in Normandy; the Allies planned to deploy VCPs after D-Day, but they could not have functioned effectively during the landings. |

Beyond this, the lack of intelligence and preparatory activity that typified CAS strikes meant that pre-planned attacks were always far more likely to achieve mission success, and it was often far more difficult to judge whether CAS had successfully dealt with enemy targets. Today, aircraft targeting pods collect strike video, and a ground commander with access to live Full-Motion Video (FMV) can usually advise if his intent has been fulfilled or if further strikes are needed, but the more limited view of the battlefield possessed by ground troops in the Second World War restricted the scope for accurate assessment.

For any air force seeking to employ combat air power in an effective and efficient way - to achieve maximum operational effect and economy of force - the attraction of pre-planned targeting is obvious. By contrast, CAS is haphazard, unscientific and uneconomic. Measured against operational objectives, it produces a very low return in relation to the effort involved.

However, it should also be remembered that, in June 1944, CAS had never before been used in an amphibious landing in the European theatre, and even in the Pacific it had overwhelmingly been employed against inland targets, after the initial landing phases of amphibious operations. The difficulty lay in achieving the necessary level of integrated air and ground coordination without the essential shore-based supporting command, control and communications capabilities. Shore-to-air communication on D-Day was not a practical proposition; shore-to-ship communication was problematic enough. Measures were instituted to allow air support requests to be passed back from the beachheads to the UK-based tasking agencies, but the official history records that ‘on the whole, the Army was unable to offer any worthwhile targets, and armed reconnaissance missions were in the majority.’ Armed reconnaissance involved patrolling and searching for targets of opportunity without prior intelligence or guidance from the ground, and without any measures to prevent fratricide.

The unit diaries of the RAF’s Typhoon squadrons confirm the official history’s version of events. D-Day was a definite anti-climax. Squadrons tasked early against pre-planned targets struggled to find them in the prevailing overcast weather conditions, and some of their missions were aborted altogether. Squadrons assigned to on-call air support remained on the ground. The pilots and their aircraft waited patiently, but hardly any tasking materialised. The beach-heads were too disorganised; communications were poor; the location of German opposition was too uncertain.

When these squadrons finally became airborne later in the afternoon, their armed reconnaissance missions chiefly took them well inland to attack German forces moving towards the coast. A significant strike effort against targets west of the port of Cabourg was probably requested by the Navy but was desperately risky given the presence of British airborne troops in the area and the lack of any deconfliction measures. The well-known incident earlier on D-Day in which the headquarters staff of the 3rd Parachute Brigade (part of 6 Airborne Division) came under air attack must be considered in this context, although the perpetrators of this strike were almost certainly misidentified by their commanding officer.

|

| Smoke and cloud obscuring Sword beach on D-Day. |

|

| The experience of many Typhoon pilots on D-Day; a long wait for support requests that never materialised, followed at the end of the day by 'armed recce'. |

In Europe, a form of CAS was first employed to support an amphibious landing in Operation Infatuate - the assault on the Dutch island of Walcheren in November 1944. Although it was not required for Infatuate 1, at Vlissingen, it played a vital role in Infatuate 2 at Westkapelle. By this time, CAS TTPs were very well established on the continent along with the all-important C2 architecture. There was no communication between the landing beaches and the aircraft overhead, but pilots could talk directly to the headquarters ship during the assault on Westkapelle. Moreover, before Infatuate, the Allies had captured the so-called Breskens Pocket on the south bank of the Scheldt estuary and located a Forward Control Post there to support the beach landings, which targeted the opposite side of the river.

CAS was also effective during Infatuate 2 because the main German targets were large and very obvious gun emplacements sited in a single perimeter line on a sea wall or at the top of sand dunes; all the second-line inland German defences had been flooded and abandoned. Targets were easy to spot from the air without detailed guidance from the ground, and there was very little anti-aircraft fire. In summary, the factors that allowed CAS to be successfully employed in Infatuate 2 were simply not present in Normandy five months earlier.

|

| A Typhoon strike on German defences at Westkapelle. |

|

| The targets: gun emplacements easily visible on top of the sea wall at Westkapelle. The Normandy target array was far more challenging. |

Beyond this, the assertion that the Allied air forces should have provided more tactical air support on D-Day is partly based on a failure to grasp the capabilities and limitations of the RAF and USAAF fighter-bomber squadrons in Normandy. For sure, tactical air power played a vital role. It prevented German assembly, movement and manoeuvre in daylight, thus making counter-attack virtually impossible. It broke up German armoured formations heading towards the beaches after D-Day and played a key part in halting the German offensive at Mortain in August. It also inflicted crippling losses on German soft-skinned vehicles throughout the campaign. To this extent, the decisive value of tactical air power cannot be contested.

Yet tactical air power in the Second World War provided nothing remotely comparable to modern-day CAS, which has been transformed by the development of precision-guided bombing over the last thirty years. Today, when ground units conducting offensive operations run into resistance, they can call in precision air support to eliminate the enemy forces and allow the advance to continue; single air strikes can often be relied on to achieve the required effect. Such engagements can also take place from medium altitude, where the absence of tangible threats to the aircraft allows ample time for extended pre-strike observation of the target and for target acquisition. This offensive support capability just did not exist in 1944.

The aircraft assigned to the tactical support role in Normandy were almost all converted fighters designed for air-to-air combat that offered the pilot only a limited view of the ground. This complicated the task of target recognition, and extensive loitering at low level in search of well-concealed targets protected by potent mobile light flak quickly proved to be an extremely unhealthy practice. The 151 names on the Normandy Typhoon memorial at Noyers Bocage bear witness to this basic truth. Target acquisition, strike and withdrawal had to be executed rapidly, and, for offensive support, this required guidance from the ground or prior intelligence, both of which were invariably lacking.

The scope for finding targets without such direction was also reduced by the limited endurance of some of the fighter-bombers, particularly the RAF’s Typhoons and Spitfires. Flying from southern England with a full load of rockets, Typhoons had a very limited loiter capability over Normandy. Therefore, if not assigned immediately to targets after their arrival over the landing area, they could hold for only a short time before return to base became essential. The alternative was the English Channel. This is why it was so important to establish forward airfields in Normandy at the earliest possible moment - a central feature of Allied planning.

|

| An extensively flak-damaged 182 Squadron Typhoon and a very lucky pilot; 151 of his comrades were not so fortunate. |

|

| Endurance was a major constraint; these Spitfires were based on the southern English coast, carried long-range tanks and were soon using landing grounds in Normandy to refuel. |

|

| Effective tactical air power required an RAF ground presence in Normandy; these RAF trucks were moving inland from Gold beach on 6 June 1944. |

The difficulty of target identification helps to explain why the role of forward controllers was so important. Yet the controllers’ task was by no means simple. Ideally, they had to be able to see the target and communicate with aircraft overhead - a challenging proposition that often placed them in the firing line. The use of contact cars - converted armoured vehicles - developed during the Normandy campaign for this reason but did not entirely solve the problem, and there were several casualties, notably during Operation Goodwood in July. There were also frequent ground-to-air communications failures.

Most of all, the heavier weapons employed by the fighter-bombers - rockets and bombs - were very inaccurate and achieved more through morale effect than physical damage. Cannon and machine gun strafe was far more accurate and was substantially responsible for the widespread attrition of German soft-skinned vehicles, but it was ineffective against reinforced concrete, dug-in positions and armour. It was for this reason that the Allies repeatedly resorted to using heavy bombers in support of major ground offensives as the Normandy campaign progressed.

|

| Rocket projectiles were effective against larger fixed targets and exerted considerable morale effect, but they were very inaccurate. |

|

| Cannon or machine gun strafe was more accurate, but had little utility against prepared defences or armour. |

Of course, there were occasions when the fighter-bombers provided effective offensive air support under CAS procedures, particularly in post-Normandy pursuit operations, when enemy positions along routes of advance were well known. But the TTPs had evolved significantly by that time, and circumstances were rarely so favourable. One example of CAS being used to provide offensive air power is provided by the RAF Typhoon strikes mounted in support of XXX Corps on the first day of Operation Market Garden, in September 1944. However, the Typhoons’ intervention that day was highly choreographed, and they were operating a cabrank over a single road along which, sooner or later, German opposition was certain to appear.

Given the proven limitations of Allied tactical air support in an offensive role in the Normandy campaign, there was no valid case for deploying massed fighter-bombers over the beaches on D-Day. Arguments to this effect appear even more suspect if the true complexity of the tactical air support task is taken into account. Yet this was not only a matter of tactics, procedures and capabilities. On 6 June 1944, the Allied amphibious landing plan was substantially based on UK doctrine and, of necessity, emphasised surprise rather than the extended bombardments that preceded American landings on the Pacific islands. In Normandy, Allied troops would hit the beaches shortly after daybreak and at low tide to ensure the German beach obstacles were not submerged. The time available for preparatory fire support would be extremely limited.

From the air perspective, this would not have allowed for multiple consecutive waves of fighter-bombers to attack the Atlantic Wall and achieve any significant effect before the landings started. The Allied air forces had to find a way to deliver the largest possible volume of munitions against the German defences in the shortest possible time, and this pointed clearly towards the use of heavy bombers. They could bomb in a set time period before the landing forces beached, so reducing the risk of fratricide. Within the same period, fighter-bombers would only have been able to offload a fraction of the weight of ordnance that the larger bombers could deliver. The remainder of the fighter-bomber contribution would then have had to be made during the landings, accepting all the problems involved in target location and combat identification.

The problem with the bombing plan is well known and requires no detailed consideration here. On D-Day, thick cloud cover prevented the VIII Air Force from bombing the German defences accurately where four out of five beaches were concerned (the other, Utah, was accurately bombed by IX Air Force Marauders from low altitude).

Nevertheless, given the minimal effect that the fighter-bombers would have achieved in the time available for preparatory fire support, there was an obvious logic in attempting to use the heavies, and they would probably have bombed far more accurately in the clear weather that Eisenhower and his senior commanders banked on. Their failure did not deny fire support to the landing forces, for a significant bombardment role was also assigned to the Allied navies.

|

| VIII Air Force bombs intended for Sword beach ironically blanketed Strongpoint 'Morris', 3km inland, but missed 'Hillman' (bottom of photo). |

|

| Incredibly, 77 years later, the fields of Normandy still bear the scars. |

The use of air power in support of the Allied landings on D-Day was also substantially guided by perceptions of the primary German threats. During the pre-Overlord deliberations on how air power could best support the landings, Allied planners paid considerably more attention to the main German coastal defence batteries than the beach defences. This focus reflected the lessons identified after the Dieppe landings in 1942 and contributed to the fact that a far greater air effort was directed against the batteries. The Luftwaffe was also identified as a major threat, which explains the immense air superiority effort mounted by RAF and USAAF fighter squadrons over the beaches. The third threat was posed by German counterattacks into the landing area. Hence, during the later hours of D-Day, much of the Allied tactical air effort was directed against German forces moving towards the beaches, as we have seen. This role accorded far more with the strengths of the tactical air forces than offensive support against static and well prepared defensive positions.

In the event, for a variety of reasons that included preparatory bombing, the larger coastal batteries offered little resistance on D-Day, and the Luftwaffe could only react to the landings on a limited scale. Overcast weather impeded the Allied fighter-bomber squadrons for part of the day, so that they were unable to prevent 21st Panzer Division elements (that had already been positioned well forward) from moving into the area north of Caen, but they did attack German tanks and other vehicles approaching Caen from the south and east, and the tactical air forces subsequently played a key role in preventing the deployment of other enemy formations, notably Panzer Lehr.

Where would CAS have made a difference on D-Day? Four out of the five beaches were captured quickly, despite some heavy fighting. The key delays in the advance inland were chiefly the result of disorganisation and slow assembly after the landings, exacerbated by minefields and the rapidly rising tide. The subsequent British failure to reach Caen from Sword occurred partly because of determined German resistance at Strongpoint Hillman, but nothing in the record of the Allied fighter-bomber forces in the Normandy campaign suggests that they might have been able to evict the Germans from this formidable defensive complex. Moreover, the difficulty of employing close or direct air support against Hillman is perfectly illustrated by the British failure to bring naval fire support to bear. With the cruisers and destroyers deployed in strength just off the beaches, barely a stone’s throw away, it proved impossible to direct the fire of a single vessel on to the Hillman fortifications.

|

| More detailed imagery of Hillman. |

|

| Allied tactical air support would have exerted little impact on Hillman's defences. |

Otherwise, the Canadian troops that landed at Juno penetrated further inland than any other Allied landing force, and the British who came ashore at Gold captured critical follow-on objectives like Bayeux and Arromanches. The American landings at Utah beach benefited from successful preparatory bombing from IX Air Force, as we have seen, but a significant fighter-bomber effort thereafter would have been rendered virtually impossible by the presence inland of thousands of American airborne troops.

The only landing that ran into severe difficulty and might have benefited from CAS was the American operation at Omaha. However, at Omaha, virtually all communication from the beach failed, and there would thus have been no means to request CAS or any other type of tactical air strike. As it was, naval ships had to fire on the German defences without guidance from the landing forces, an approach that caused at least one serious fratricide incident, when US Navy destroyers bombarded the village of Colleville-sur-Mer after it had been captured by American ground troops. The severity of the losses involved, relative to casualties inflicted by the Germans, should not be underestimated. Captain Joseph Dawson, who commanded G Company, 16th Infantry, 1st US Infantry Division, recorded that 'we suffered the worst casualties we had the whole day - not from the enemy, but from our own Navy.'

|

| Colleville church, targeted repeatedly by unguided naval bombardment with disastrous results. |

Yet even with functional communications, it would not have been easy to call in effective air or naval fire support. Much of the German fire onto the beach was indirect and came from inland positions that the landing troops could not see. Many of these took the form of carefully concealed trenches and dugouts, or weapons deployed under natural cover or in farm buildings. The larger and more visible concrete casemates of the Atlantic Wall were only part of the problem, and the beach remained under heavy fire long after they had been captured.

By focusing on tactical air power and misrepresenting the reasons for its limited role over the beaches on D-Day, it is possible to generate an entirely false picture of Allied air forces that were uncooperative and averse to supporting the troops who landed in Normandy on 6 June 1944. The reality is that the Normandy landings were the culmination of an extended and enormous air operation that pressed the Germans on to the defensive, destroyed their air force, isolated the landing area, photographed and mapped it in minute detail, sustained the Allied deception plan, dismantled German early warning, intelligence and C2 networks and bombed their coastal batteries.

On D-Day, air power continued to isolate the landing area in the air, on land and at sea; it delivered the airborne forces; the USAAF sought to drench the beach defences with bombs, albeit unsuccessfully; the reconnaissance effort continued; the first echelons of the tactical air forces came ashore with the aim of establishing bases in Normandy at the earliest possible moment and the C2 and logistical infrastructure necessary to provide tactical air support to ground forces; radar units also landed and played a crucial role in the air defence of the lodgement area.

The employment of air power in support of a ground campaign does not simply involve CAS or the dispatch of combat aircraft on haphazard armed reconnaissance missions to attack an enemy’s forward positions (assuming they can be found). It involves harnessing all available air power to missions from which the ground campaign will benefit. Many of these may be executed far beyond the front line; equally, the most intensive and decisive air operations will not necessarily coincide with decisive ground operations. The main air operations in support of the Normandy landings began two months before the troops came ashore; more limited air operations started long before that. No less important were air operations immediately after D-Day, which prevented a German counterattack against the Allied beachhead that might have driven the landing forces back into the sea. It is only by ignoring or misrepresenting such fundamental differences between the air and ground environments, and by interpreting air support for ground forces in the narrowest possible tactical sense, that an entirely fictitious depiction of tactical air power on 6 June 1944 can be sustained.

Thank you for providing this, very good!

ReplyDeleteWe should perhaps remember that Fighter Direction Ships (HMS Largs and Bull) had been used in Dieppe, during Operations Torch, Corkscrew and Husky with increasing levels of success and the Navy FOO was killed which prevented the fire from the nearby warships suppressing the 'Hillman' defensive position in the way it had done in the nearby 'Morris' defensive position. FDTs 216 and 217 were nearby with FDT 217 covering the Hillman area. Moreover, Patrol Areas X-Ray, Easy and Charlie were very close to Hillman. All that was needed was a way to join the dots, by matching aircraft to the target. Coordinated suppressing fire was all that was needed, as the Army eventually overcame the defences without excessive use of firepower.

ReplyDeleteThanks, but the focus here is direct air support. Ship-based C2 played a role in the assault on Westkapelle in November 1944, but in the context of specific and clear intelligence on the location of German opposition and a tasking chain that provided for continuous fighter-bomber presence over the landing area. In Normandy, this was impossible and air support had to be requested through the UK-based tasking channels and passed to UK-based squadrons, which had then to fly to Normandy. Hardly any requests were received during the landing phase that clearly specified the location of German opposition. On the failure of naval bombardment at Hillman, I included this because it perfectly illustrates the difficulty of organising precise fire support in such circumstances. The issue of exactly why it failed (the death of the FOO) is less important than the fact that it failed.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI see, that makes sense. I should correct my earlier post too as I wrote it from memory. Two of the three FOB parties that landed on Sword Beach were made inoperable and only Captain Llewellyn was able to control fire from the six-inch guns from the cruiser 'Dragon' and the destroyer 'Kelvin' and his LCA received a direct hit killing him. I seem to recall that he was a relative of the cricketer David Gower, but that as before is from memory.

DeleteActually the air programme had pre-arranged targets in support of the landings on June 6th by 83 Group RAF and the fighter bombers, namely the Typhoons, were each assigned targets, with No.143 Wing RCAF being in first. However, like Dieppe, the RAF were awaiting for a mass reaction by the Luftwaffe which never really happened, which is why you see a big change on tactical recces from June 7th onwards. As for the USAAF on June 6th, that is not my area of focus. ;)

ReplyDeleteNot sure I understand your meaning. The allocation of of pre-arranged targets to some squadrons is recorded above and in the Typhoon ORB extracts linked to this blog. However, several of these missions were aborted. Other squadrons were not assigned planned targets. They were 'on-call' on D-Day and waiting for tasks that rarely materialised during the landings. Some were tasked against targets later in the day; others were sent on armed recce, seeking targets of opportunity, as the ORBs clearly show. This has nothing to do with the provisions made for providing air cover against the Luftwaffe.

ReplyDeleteNot understanding my meaning in what sense? Yes, not all the Typhoon squadrons had pre-arranged targets. However, the leader of the F/B squadrons or wings were to check in with the FDT's first to see if there were other pressing areas/targets to attack before proceeding to their assigned target. What became very apparent were the lack of direct support calls from the army during the early stages of the landings, hence, utilizing the F/Bs in armed recces, which became the norm as they obtained more intel value with these then from the actual Tac/R aircraft. And, the army was also calling for these armed recces as well.

ReplyDeleteNo disagreement that I can see. You accept my point that not all Typhoon squadrons had pre-arranged targets. You also talk about armed recce but - my point again - armed recce is not CAS. CAS involves detailed integration between air and ground forces, which was impossible on D-Day.

ReplyDelete