The last 75-year anniversary of 2019 is the Battle of the Bulge, the popular name for the German Ardennes offensive of December 1944. The Ardennes is invariably treated as a land battle; the role of air power tends to be forgotten. Yet the RAF and the USAAF made a critically important contribution to the Allied victory.

|

At 0530 hours in the rain and mist of Saturday 16 December 1944, a barrage of some 1,600 artillery weapons heralded the launch of Nazi Germany’s last western counter-offensive of the Second World War. Targeting the densely forested Ardennes region of Wallonia in eastern Belgium, northeast France and Luxembourg, the German advance extended along a front of some forty miles, from Monschau, south of Aachen, to Echternach, just above the junction of the Saar and Mosel rivers.

Planning for the counter-offensive began in the middle of October. Three armies consisting of eight panzer divisions and 16 panzer grenadier and infantry divisions, were assembled within the area of Army Group B. They were tasked to destroy the Allied armies positioned between Antwerp and Bastogne and seize the vital supply bases of Antwerp, Liege and Brussels. The Sixth SS Panzer Army, was given the most important role of seizing crossings over the Meuse north and south of Liege. It was then to swing north and capture Antwerp.

In the centre, the Fifth Panzer Army, re-equipped after its mauling in Normandy, was to penetrate the weakly held Ardennes front on the axis Bastogne-Namur and hold the line of the Meuse around Dinant. Afterwards, it was to extend northwards to cover Brussels and Antwerp and so protect the Sixth SS Panzer Army. The resuscitated Seventh Army was to strike towards the Meuse from Echternach, but its main task was to safeguard the flanks of the two Panzer Armies from the south and south-west.

Absolute tactical surprise was vitally important to the success of the operation, and the Germans recognised they would need to secure the Meuse crossings within 24 hours if they were to stand any chance of achieving their objectives.

Another critical factor was the provision of sufficient fuel for their mechanised forces. Allied bombing and the loss of the Romanian oil fields had caused German supplies to run dangerously low. It proved necessary to delay the operation to provide time to increase stocks, yet they were known to be inadequate on the eve of the offensive, and the Germans were forced to gamble on the capture of Allied fuel depots. Moreover, the need to conserve fuel left them heavily dependent on rail transport to bring troops and vehicles close to the front. This helps to explain why the Allied strategy of railway interdiction subsequently proved so effective.

Finally, although a revitalised Luftwaffe planned to provide air cover for the ground advance on a considerable scale, the German plan nevertheless relied on the prevalence of poor weather to counter-balance Allied air superiority.

Allied intelligence had observed signs of a German build-up to the east of the Ardennes before the offensive was launched. In the last week of November, SHAEF commanders were advised that air reconnaissance, taking advantage of an improvement in the weather, had identified rail movement through the Ruhr to the Cologne-Dusseldorf district. The lines from Darmstadt and Frankfurt were also busy. Four panzer divisions of Sixth SS Panzer Army were believed to be in reserve in the Cologne sector. Similarly, the US IXth Tactical Air Command obtained evidence of large armour and vehicle concentrations in the Eifel district, which was passed to General Hodges of First US Army.

Another critical factor was the provision of sufficient fuel for their mechanised forces. Allied bombing and the loss of the Romanian oil fields had caused German supplies to run dangerously low. It proved necessary to delay the operation to provide time to increase stocks, yet they were known to be inadequate on the eve of the offensive, and the Germans were forced to gamble on the capture of Allied fuel depots. Moreover, the need to conserve fuel left them heavily dependent on rail transport to bring troops and vehicles close to the front. This helps to explain why the Allied strategy of railway interdiction subsequently proved so effective.

Finally, although a revitalised Luftwaffe planned to provide air cover for the ground advance on a considerable scale, the German plan nevertheless relied on the prevalence of poor weather to counter-balance Allied air superiority.

Allied intelligence had observed signs of a German build-up to the east of the Ardennes before the offensive was launched. In the last week of November, SHAEF commanders were advised that air reconnaissance, taking advantage of an improvement in the weather, had identified rail movement through the Ruhr to the Cologne-Dusseldorf district. The lines from Darmstadt and Frankfurt were also busy. Four panzer divisions of Sixth SS Panzer Army were believed to be in reserve in the Cologne sector. Similarly, the US IXth Tactical Air Command obtained evidence of large armour and vehicle concentrations in the Eifel district, which was passed to General Hodges of First US Army.

Nevertheless, when the offensive was launched on 16 December, it achieved complete tactical surprise and penetrated the entire length of the Allied front. The initial air response came from the IXth Air Force, which flew over 1,200 sorties on 16 December, attacking observed German ground movements between Cologne and Trier in the face of determined Luftwaffe opposition. The following day, the weather deteriorated, but American Thunderbolts nevertheless struck transport along the roads through Malmedy and Stavelot.

By the 17th, the Allies had agreed that all available aircraft from Second Tactical Air Force (2 TAF) should support the IXth Air Force on the following day, leaving behind the minimum number to protect the British sector of the front. US aircraft were to give close support to the First and Third US Armies, while the British provided air cover and, in addition, operated east of a line determined by the IXth Air Force. However, nearly all the Typhoons dispatched on 18 December flew abortive missions because of low cloud. That night, 2 TAF Mosquitoes were ordered to search roads leading from the Rhine towards the front in an area stretching from Düsseldorf as far south as Trier. With the help of navigational aids, they bombed cross-roads and rail junctions and attacked several motor convoys.

Meanwhile, Allied attention turned towards deeper targets - the railways, marshalling yards, roads, junctions and bridges sustaining the German advance. Their attack was assigned to the VIIIth Air Force and Bomber Command and began on the night of 17/18 December.

On the 19th, the Allies reorganised their command structure: British and American forces north of the German salient were assigned to Montgomery, while US forces further south remained under Bradley. Air command and control was altered accordingly to give Coningham command of the USAAF's IXth and XXIXth Tactical Air Commands (which normally supported the US First and Ninth Armies). A reinforced XIXth TAC was tasked to support Patton’s Third Army in the south, and the IXth Air Force was strengthened by XIIIth Air Force elements.

Extremely poor weather from the 19th to the 22nd severely disrupted operations by the Allied tactical and strategic air forces. Although Bomber Command attacked the important railway centre of Trier on the 21st, other operations were frustrated by dense cloud cover over the main target areas. During this period, the 5th Panzer Army was forced to bypass Bastogne but achieved more rapid progress towards the Meuse than the 6th SS Panzer Army to the north, which was delayed by stubborn American resistance, fuel supply and other logistical and transport problems.

The weather finally cleared on the 23rd, and conditions remained relatively fine until the 28th. Over these five days, the totality of Allied air power was committed to an all-out effort to halt the German advance. There was no time to devise a complex air plan, but it was clearly essential to delay the German thrust to the maximum extent, while sufficient ground forces were assembled for a counter-attack.

Heavy and medium bombers were sent out to strike communications centres and bridges stretching from directly behind the front to the Rhine and beyond. Meanwhile, the fighter-bombers were tasked to harass movement in the German salient to delay the road convoys supplying the forward troops from the railheads, and blunt the German spearheads by attacking their armour. Once German lines of communication were fully extended, the heavy and medium bombers sought to create choke points inside the salient to delay movement to and from forward areas.

Heavy and medium bombers were sent out to strike communications centres and bridges stretching from directly behind the front to the Rhine and beyond. Meanwhile, the fighter-bombers were tasked to harass movement in the German salient to delay the road convoys supplying the forward troops from the railheads, and blunt the German spearheads by attacking their armour. Once German lines of communication were fully extended, the heavy and medium bombers sought to create choke points inside the salient to delay movement to and from forward areas.

|

| Giessen - a deep but vitally important railway target attacked by Bomber Command. |

|

| By contrast, Trier lay only a short distance behind the battle area. |

Persistent attacks on railway centres and bridges had the effect of pushing back the all-important German rail-heads as far as the Rhine or even further east. This magnified the strain on motor transport, which in turn consumed fuel that was desperately needed to sustain the offensive. The state of the roads in the wintry weather and the poor condition of many vehicles aggravated transport difficulties. Against this background, the movement of supplies and reinforcements to the more forward German elements was severely delayed or even blocked completely.

Among the communication centres to suffer considerable damage were the important junctions of Bitburg, where movement was completely halted by the end of December, and Gerolstein, which could only be approached by one road. At Prum, motor transport was unable to pass through the town, and detours had to be constructed to bypass it. Strikes on bridges west of the Rhine (largely the work of US heavy and medium bombers), such as those across the rivers Ahr and Mosel, also helped to obstruct rail traffic heading for the front.

By targeting rail centres along the Rhine from Cologne to Coblenz, the Allied air forces drove German traffic out of the river valley as far east as Karssel and Wurzburg, exacerbating the delays and re-routings. The cumulative effect of these air attacks was such that rail travel west of Giessen became virtually impossible in daylight, except when bad weather prohibited flying. The impact was felt as far back as Hamm and Nuremburg.

Among the communication centres to suffer considerable damage were the important junctions of Bitburg, where movement was completely halted by the end of December, and Gerolstein, which could only be approached by one road. At Prum, motor transport was unable to pass through the town, and detours had to be constructed to bypass it. Strikes on bridges west of the Rhine (largely the work of US heavy and medium bombers), such as those across the rivers Ahr and Mosel, also helped to obstruct rail traffic heading for the front.

By targeting rail centres along the Rhine from Cologne to Coblenz, the Allied air forces drove German traffic out of the river valley as far east as Karssel and Wurzburg, exacerbating the delays and re-routings. The cumulative effect of these air attacks was such that rail travel west of Giessen became virtually impossible in daylight, except when bad weather prohibited flying. The impact was felt as far back as Hamm and Nuremburg.

|

| Road, rail and bridge attacks executed by the RAF and the USAAF during the Ardennes offensive. |

Not only was the flow of supplies interrupted but reinforcements took days to reach the front. Many troops were forced to detrain east of the Rhine and had to make their way forward as best they could. On 28 December, for example, reinforcements for 9 Panzer Division had to detrain near Siegburg (south of Cologne) and then proceed on foot via Bonn for a distance little short of 100 miles. On about the same date, reinforcements for 104 Panzer Grenadier Division travelled for six nights to make the rail journey from Siegen to Bendorf, near Coblenz, and from that point had to march to Mayen, west of the Rhine. Reinforcements for the Volks Grenadier divisions supporting the panzer formations were held up for days because of bomb damage at Cologne, which was described by a USAAF Air Intelligence Summary on 7 January 1945:

Cologne/Nippes. After moderate damage sustained in attacks on 21 and 23 December by RAF formations, the marshalling yards here were very heavily hit on the 24th, again by the RAF. Two days later, the yards as a whole were completely unserviceable, with every siding cut in at least one place, and the locomotive depot and repair shops were further damaged. With the yard heavily loaded at the time of attack, a considerable quantity of rolling stock was derailed and damaged.

Even during the bad weather that characterised the first week of the offensive, the Allies achieved a substantial air effort. In that period, Bomber Command, operating by day and night, flew over 2,000 sorties against communication targets, while the VIIIth Air Force flew over 1,700. Constrained though they were by poor visibility, 2 TAF flew about 2,280 sorties and the IXth Air Force 3,970 sorties during this week.

Nevertheless, once the weather cleared, the scale of effort was magnified many times over. By 27 December, the armoured thrust to the Meuse had been halted and the German operation to seize Antwerp, which depended entirely on speed and surprise, had failed. This was before the Allied ground forces counter-attacked in strength. By the 27th, the RAF and USAAF had flown a total of 34,042 sorties since 16 December, most of which were directed against the German attack.

Cologne/Nippes. After moderate damage sustained in attacks on 21 and 23 December by RAF formations, the marshalling yards here were very heavily hit on the 24th, again by the RAF. Two days later, the yards as a whole were completely unserviceable, with every siding cut in at least one place, and the locomotive depot and repair shops were further damaged. With the yard heavily loaded at the time of attack, a considerable quantity of rolling stock was derailed and damaged.

Even during the bad weather that characterised the first week of the offensive, the Allies achieved a substantial air effort. In that period, Bomber Command, operating by day and night, flew over 2,000 sorties against communication targets, while the VIIIth Air Force flew over 1,700. Constrained though they were by poor visibility, 2 TAF flew about 2,280 sorties and the IXth Air Force 3,970 sorties during this week.

Nevertheless, once the weather cleared, the scale of effort was magnified many times over. By 27 December, the armoured thrust to the Meuse had been halted and the German operation to seize Antwerp, which depended entirely on speed and surprise, had failed. This was before the Allied ground forces counter-attacked in strength. By the 27th, the RAF and USAAF had flown a total of 34,042 sorties since 16 December, most of which were directed against the German attack.

Tonnage

Bomber Command 4,193 15,702

VIIIth Air Force (incl fighters) 8,404 10,302

IXth Air Force 11,316 6,643

2nd TAF 5,971 550

1st (Prov.) TAF 3,119 1,511

RAF Fighter Command 1,039

-------- ---------

Total 34,042 34,708

Out of the total weight of bombs dropped, about 23,830 tons were employed against railway and other communication targets serving the battle area. The Belgian town of St Vith provides one of the best illustrations of how effectively communications targets were interdicted. As well as a railway, roads to Vielsalm, Laroche, Recht and Houffalize passed through St Vith and made it the most important road junction on the Sixth SS Panzer Army front. On Christmas Day, Marauders struck the town, causing considerable damage. The Germans made frantic efforts to clear the streets of rubble during the night. By the morning, a little one-way traffic was possible.

However, at 1500 hours on the 26th, the town was bombed by 294 Lancasters, which dropped 1,138 tons of high explosive. Huge craters in the roads made all routes through St Vith impassable. German sappers, who worked on the St Vith-Malmedy road, stated that it was beyond repair for a distance of from two to three kilometres. On the following day, St Vith was placed out of bounds to both troops and civilians, and military traffic used secondary roads as bypass routes, a distance of about two miles to the north and south. One small bypass in the town itself was cleared through the railway yard on the 27th.

|

| An early strike on St Vith. |

|

| The Bomber Command attack. |

|

| A higher-altitude image of the raid. |

|

| The aftermath. |

Of all the attacks on choke points during the Ardennes battle, this was the most effective. Clearance work did not begin in earnest until 29 December, and the roads through the town were still impassable to traffic on 3 January. More German engineers arrived on the 8th, but they were mainly tasked to keep open the by-pass north of St Vith. Attacks by fighter-bombers constantly interrupted repair work, while long-range American artillery intermittently shelled the area. By 11 January, 16 days after the last air bombardment, all roads running through the town remained blocked. Only the junction of two routes leading to Malmedy and Monschau (located in the northern outskirts) had been opened.

The impact of air attacks on German convoys between the rail heads and the front was no less pronounced. It is evident that, when the weather initially improved, the Allied tactical air forces were presented with something of a Turkey shoot. From then on, German vehicles moving along roads through the salient in daylight were running the gauntlet. From the 23rd to the 26th, 2 TAF reported that some 486 attacks on ‘MET’ had destroyed 132 vehicles and damaged 280. Bearing in mind that many more sorties were flown by the Americans over the same period, the total level of destruction wrought on the German columns would have been greater still. One Allied analyst estimated that the two tactical air forces might have destroyed or damaged at least 500 vehicles on the 24th alone, and added:

In addition to whatever effect destruction of vehicles and loads may have had, there is another effect, which may have been more important. The presence of the fighter-bombers caused the enemy to take cover when aircraft were seen or heard, and to proceed mainly at night. The delay so induced must have been considerable.

The 2 TAF Operational Research Section examined the impact of Allied air attacks on the German offensive and reached the following conclusions. The heavy and medium bomber attacks had struck both railway and road systems, targeting key points, including detraining stations, bridges and marshalling yards. The weather did not allow a large effort during the first week of operations, when bomb release averaged about 500 tons per day; however, during the second week, the weight of bombs rose sharply to over 1,500 tons per day and remained at that level.

The German rate of advance continued at about 20 km per day until the 23rd. It slowed on the 24th and ceased altogether on Christmas Day. There was no sudden change in resistance on the ground to account for the abrupt cessation of the advance, whereas the timing of the air effort fits the events perfectly. Although some of the effect of bombing on lines of communication would have been felt at the front within 24 hours, a two-day time lag would represent a more reasonable allowance for the full effect on supplies travelling from the bombed area to the forward troops, and this more extended cause-and-effect sequence was reflected in the measurable deceleration of German progress, the intensification of Allied bombing, and Allied intelligence reports revealing significant shortages of fuel and ammunition among forward German units.

The impact of air attacks on German convoys between the rail heads and the front was no less pronounced. It is evident that, when the weather initially improved, the Allied tactical air forces were presented with something of a Turkey shoot. From then on, German vehicles moving along roads through the salient in daylight were running the gauntlet. From the 23rd to the 26th, 2 TAF reported that some 486 attacks on ‘MET’ had destroyed 132 vehicles and damaged 280. Bearing in mind that many more sorties were flown by the Americans over the same period, the total level of destruction wrought on the German columns would have been greater still. One Allied analyst estimated that the two tactical air forces might have destroyed or damaged at least 500 vehicles on the 24th alone, and added:

In addition to whatever effect destruction of vehicles and loads may have had, there is another effect, which may have been more important. The presence of the fighter-bombers caused the enemy to take cover when aircraft were seen or heard, and to proceed mainly at night. The delay so induced must have been considerable.

The 2 TAF Operational Research Section examined the impact of Allied air attacks on the German offensive and reached the following conclusions. The heavy and medium bomber attacks had struck both railway and road systems, targeting key points, including detraining stations, bridges and marshalling yards. The weather did not allow a large effort during the first week of operations, when bomb release averaged about 500 tons per day; however, during the second week, the weight of bombs rose sharply to over 1,500 tons per day and remained at that level.

The German rate of advance continued at about 20 km per day until the 23rd. It slowed on the 24th and ceased altogether on Christmas Day. There was no sudden change in resistance on the ground to account for the abrupt cessation of the advance, whereas the timing of the air effort fits the events perfectly. Although some of the effect of bombing on lines of communication would have been felt at the front within 24 hours, a two-day time lag would represent a more reasonable allowance for the full effect on supplies travelling from the bombed area to the forward troops, and this more extended cause-and-effect sequence was reflected in the measurable deceleration of German progress, the intensification of Allied bombing, and Allied intelligence reports revealing significant shortages of fuel and ammunition among forward German units.

In the same way, the fighter-bombers also played an important part in halting the offensive. Nearly 600 sorties reported attacks on German vehicles on the 24th, and there was no reduction in the flying effort over the next few days. By the 25th, it was impossible for the Germans to make any further progress. Allied fighter-bomber missions were flown nearer to the front than bomber missions, and a time lag of one day would fit the theory that their attacks also substantially reduced the flow of supplies and reinforcements to the armoured spearheads.

The evidence did not show that any part of the indirect air effort was more important than another part. In fact, it seemed probable that attacks on distant marshalling yards and lines of communication, both behind the salient and within it, exerted effects that were complimentary and mutually reinforcing.

The 2 TAF report concluded:

(1) During the period of bad weather before Christmas when little or no flying was possible, the rapid advance continued.

(2) The first day of really heavy bombing in the rear areas coincided with a day of considerable advance by the Germans.

The evidence did not show that any part of the indirect air effort was more important than another part. In fact, it seemed probable that attacks on distant marshalling yards and lines of communication, both behind the salient and within it, exerted effects that were complimentary and mutually reinforcing.

The 2 TAF report concluded:

(1) During the period of bad weather before Christmas when little or no flying was possible, the rapid advance continued.

(2) The first day of really heavy bombing in the rear areas coincided with a day of considerable advance by the Germans.

(3) The following day, when the fighter-bombers resumed their activity, and when the effect of the previous day’s heavy bombing was beginning to be felt on the L of C, the enemy’s advance was very much reduced.

(4) The next day, when the effect of the fighter-bomber attacks on transport and that of the heavy bombing attacks in the rear, had both made themselves felt in the forward areas, the offensive came to a standstill.

|

| Typical of the German experience from 23 December: a demolished bridge, snowy fields pockmarked by exploding munitions and a road littered with destroyed or abandoned vehicles. |

The perspective of 2 TAF’s fighter-bomber squadrons on this process is well recorded in 83 Group’s intelligence summaries. After several days of relative inactivity, pilots initially struggled to find many profitable target areas. However, on Christmas Day, 83 Group recorded their most successful attacks on ground targets for some months.

The weather was good and in the areas closer behind the battle, flak was much reduced, compared with the deeper L of C covered yesterday … The general area East of MALMEDY was well searched, and excellent results achieved. Movement was scattered and much of the MET was found sheltering in small villages. The biggest concentration attacked was 80+ ….

143 Wing, released from the railway lines, produced a steady score from almost every mission, and their efforts were matched by the other Typhoon Wings.

An accompanying report on the ground situation noted:

The weather was good and in the areas closer behind the battle, flak was much reduced, compared with the deeper L of C covered yesterday … The general area East of MALMEDY was well searched, and excellent results achieved. Movement was scattered and much of the MET was found sheltering in small villages. The biggest concentration attacked was 80+ ….

143 Wing, released from the railway lines, produced a steady score from almost every mission, and their efforts were matched by the other Typhoon Wings.

An accompanying report on the ground situation noted:

Both 1st and 3rd US Armies report a considerable decrease of enemy movement and offensive activity. Much of the credit for this satisfactory state of affairs can be undoubtedly taken by the Air Forces.

The following day produced very similar results:

Practically every mission that went out came back with some MET to its credit, and for the second day in succession a very satisfactory total was achieved. The highest single score of the day came from 143 Wing, who claimed 8 MET destroyed, including 4 petrol bowsers, and 16 MET damaged near St Vith.

181 Squadron of 124 Wing, on an Immediate Support call SE of Dinant, attacked a number of tanks, reporting many of the crews killed and 2 tanks destroyed, 2 damaged. Forward troops later reported 7 tanks “knocked out”, one of which was a Royal Tiger.

There are numerous ground photographs of destroyed German tanks in the area where this engagement took place, but Royal Tigers are not in evidence. However, such was the bulk of these 68-ton monsters that several appear in high-altitude imagery of another area of the front. They belonged to the notorious Kampfgruppe Peiper, part of Sixth SS Panzer Army, which penetrated as far as the mountain village of La Gleize before running out of fuel and abandoning all vehicles. When at last the sun shone down on the Ardennes on Christmas Eve, 1944, they were captured for posterity on the surrounding slopes, just hours after Peiper and his men began their trek back to German lines (link to whole photo).

| ||

| Tigers 213 and 211 just south of La Gleize; other tanks are visible (arrowed) in the village.

|

|

| Now in the village square, Tiger 213 is by far the most famous resident of La Gleize. |

|

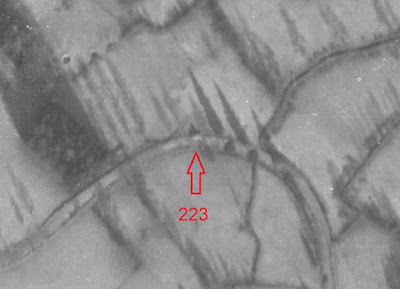

| Tiger 223, east of the village, was abandoned early in the battle after losing a track. |

|

| A ground photo of Tiger 223 - minus one track - after the Americans captured La Gleize. |

|

| Tiger 334 was deployed north-east of La Gleize. |

|

| A ground view of the same tank. |

The employment of air power in the Ardennes was not solely concerned with offensive air operations. The Allied strategic and tactical reconnaissance squadrons also played an important role. Air imagery provided ground commanders with much valuable information on the movement of enemy divisions directly behind the front, and reports were supplied on communications targets that were of inestimable value for planning interdiction strikes from one day to the next. As soon as the weather over the Ardennes improved, Allied commanders benefited from far better situational awareness than their German adversaries.

Equally significant was the role of air transport, notably parachute and glider-borne resupply to the beleaguered garrison of Bastogne, despite very poor weather conditions and strong German opposition. Moreover, the assembly of reserve ground formations for the Allied counter-attack in the New Year was accelerated by the airborne deployment of an entire division to the continent from the UK.

Equally significant was the role of air transport, notably parachute and glider-borne resupply to the beleaguered garrison of Bastogne, despite very poor weather conditions and strong German opposition. Moreover, the assembly of reserve ground formations for the Allied counter-attack in the New Year was accelerated by the airborne deployment of an entire division to the continent from the UK.

|

| German ground forces showed up well against the snow in night reconnaissance imagery. |

|

| Taken on 24 December, this image captures the Baugnez road junction, scene of the infamous Malmedy massacre (arrowed). |

|

| Another RAF air reconnaissance image showing American Waco gliders littering the fields around Bastogne. |

At the same time, the Allied fighter forces frustrated the Luftwaffe’s attempts to secure temporary air superiority west of the Rhine. Although flying an average of around 600 sorties per day, the Luftwaffe exerted little influence on the course of the battle. At best, they diverted a proportion of the Allied fighter and fighter-bomber squadrons from attacking ground targets for a time, but their efforts proved impossible to sustain, partly because of air-to-air combat losses and partly because of Allied air attacks on German airfields.

Arguably, the Luftwaffe should have struck against the more forward Allied airfields at the start of the offensive to reduce the scale of the Allied air response as far as possible. Instead, committed to a vain effort to provide cover for German ground forces, they delayed their attack on the RAF and the USAAF (Operation Bodenplatte) until New Year's Day. Achieving complete tactical surprise, they destroyed a number of Allied aircraft that will never be established with certainty. The lower estimates suggest around 140 destroyed and 110 damaged, but more recent research points to higher figures, and one contemporary German estimate based on air reconnaissance imagery claimed 479 Allied aircraft were destroyed on the ground or in air combat, and 114 were damaged.

Arguably, the Luftwaffe should have struck against the more forward Allied airfields at the start of the offensive to reduce the scale of the Allied air response as far as possible. Instead, committed to a vain effort to provide cover for German ground forces, they delayed their attack on the RAF and the USAAF (Operation Bodenplatte) until New Year's Day. Achieving complete tactical surprise, they destroyed a number of Allied aircraft that will never be established with certainty. The lower estimates suggest around 140 destroyed and 110 damaged, but more recent research points to higher figures, and one contemporary German estimate based on air reconnaissance imagery claimed 479 Allied aircraft were destroyed on the ground or in air combat, and 114 were damaged.

However, in the process, the Luftwaffe sacrificed nearly 200 aircraft, having already lost over 700 since 16 December. Bodenplatte exerted no significant effect on the Allies but initiated the Luftwaffe’s final, terminal decline.

|

| Expensive but sustainable: an RAF Lancaster destroyed during Operation Bodenplatte. |

|

| Unsustainable attrition: one of the many German fighters shot down during the operation. |

Last, but by no means least, it is all too easy to forget the RAF's ground presence in the Ardennes in December 1944. On the 16th, the radar and signals units of 72 Wing were deployed well forward in an area extending from Vielselm in the north to Bastogne in the south, under the protection of two RAF Regiment armoured car squadrons and a rifle squadron. Often in close proximity to German forces, the Regiment squadrons subsequently acted as pathfinders, escorts and rearguards to ensure that the technical units and nearly all the highly-classified tools of their trade were withdrawn to the safety of Allied lines. What remained was destroyed before it could fall into enemy hands.