|

| A high-tide wet-shod landing at Omaha; this was the original plan for 21 Base Defence Sector, but the reality would prove very different |

Omaha Beach has an entirely justified notoriety in twentieth century military history. Popularly known as ‘Bloody Omaha’, it was the one D-Day landing beach where almost everything went disastrously wrong. The cost, in terms of manpower and equipment losses, was inevitably very high. Omaha was one of the two American landing beaches in Normandy. Nevertheless, a small British unit also came ashore there on 6 June 1944 – a unit substantially composed of RAF radar controllers and operators, communications specialists, drivers, technicians and mechanics. They were known as 21 Base Defence Sector (BDS). Their story was first unearthed by the RAF’s official historians soon after the Second World War, but it was then largely forgotten until the 50th anniversary commemorations of D-Day in 1994 helped generate a renewed interest in the Normandy campaign.

Research conducted since has added significantly to our knowledge of 21 BDS’s experience on D-Day. The results can now be consulted via at least two highly informative websites and a number of individual online contributions to broader historical recording. These invaluable resources are only limited in their utility by the website format, which breaks the story down into a multiplicity of disparate elements. It was felt that there was, perhaps, a case for presenting a single, coherent narrative too.

The following account was primarily written with that end in mind. Its aim

is to integrate what we know about the 21 BDS landing into the wider picture of the Omaha Beach landings on 6 June 1944. Theirs was not just a random account of a group

of British forces personnel who happened to turn up at a particular place and

time to be confronted by a near-catastrophic military situation. The broader

history of Omaha, together with the more specific role, plans and training of

21 BDS all influenced the development and outcome of events. Beyond this,

detailed analysis of the tactical level provides an important insight into the

reality of the Omaha battle, which differs so fundamentally from the Hollywood

depictions and serves to highlight a number of familiar military themes, such

as command and control, ‘train to fight’, and sustainability.

The fundamentals of the 21 BDS narrative were replicated many times

across Omaha Beach that day. Theirs was a story of extraordinary human courage

and endeavour in the face of extreme adversity. But whereas the majority of the

victors of Omaha were US Army infantrymen trained specifically for their

assault role or battle-hardened by earlier campaigns, 21 BDS was a British

radar unit that somehow prevailed through the leadership of a

second-in-command, a padre, and medical and technical officers of exceptional

ability and resourcefulness.

Bloody Omaha

Omaha is a long, flat sandy beach backed by high bluffs. The landscape is

so obviously favourable to defence that visitors still commonly question why

amphibious landings were staged there at all. The answer is linked to the more

general Allied plan for opening a second front in Normandy. By January 1944, it

was clear that, if the landings were to succeed, a broad front had to be

established as quickly as possible, both to resist a German counter-attack and accelerate

the Allied reinforcement rate. From Ouistreham to Le Hamel (Sword to Gold Beach), the topography of

Normandy’s coast was relatively benign for invading forces, but a landing

confined to that region would have been far too narrow. The operation,

codenamed ‘Neptune’, had therefore to be extended further west. However, from

Arromanches to the base of the Cotentin Peninsula, the coast was characterised

by long stretches of high cliff. The only beach large enough for a major amphibious

assault was Omaha.

In short, Omaha had to be

taken. How, then, was this to be achieved? Omaha is a long slightly

crescent-shaped beach punctuated by four small valleys, or ‘draws’, as the

Americans called them. The only way to move an army numbering tens of thousands

of men and immense quantities of motorised vehicles, equipment and supplies off

the beach was by capturing the draws. Needless to say, this was patently

obvious to the Germans, and the draws were thus the most heavily defended areas.

The German defences began on the beach flats, which were covered with

obstacles, many of which were mined. Among other things, this reflected the

German expectation that the Allies would seek to land at high tide so that

there was minimal open beach for the assault troops to cross under fire. Above

the tide line, there was a large shingle bank, impassable to most motor

vehicles; in some places it was backed by a sea wall. On the other side of the

bank was concertina barbed wire. The dunes and marshes between the beach and

the bluffs were heavily mined.

|

| German beach defences at the D-3 (Les Moulins) draw - the most heavily fortified area of Omaha |

|

| An air photograph of the same area on the morning of D-Day |

There were trenches and machine gun nests in the bluffs and at their

summit, along with mortars and artillery batteries further back – all carefully

zeroed in on the beach. But the bluffs were less heavily defended than the

draws. At the draws, the Germans built what they called ‘resistance nests’,

consisting of concrete artillery emplacements, smaller pillboxes, machine gun

and mortar positions and extensive trench systems fronted by mines and barbed

wire. High barriers or anti-tank ditches blocked all the exits. At the Les

Moulins draw (numbered D-3 by the Americans), 21 BDS found ‘underground

passages like rabbit warrens, honeycombing the whole area’. The beach was

defended by three battalions – about 2,500 men – two of which comprised

good-quality German personnel drawn from 352 Division; the third consisted of

lower-quality Eastern Europeans.

If the Omaha landing was to succeed, an effective joint fire support

plan was essential, but it proved difficult to reconcile the need for heavy

fire support with the amphibious landing plan. The amphibious plan decreed that

the invasion force would cross the channel under cover of darkness and be

positioned for the assault before daybreak. The landings would then proceed

shortly after daybreak in co-ordination with tidal conditions. By coming ashore

soon after daybreak the Allies were seeking to achieve tactical surprise, but

it was also essential to land at low tide so that the beach obstacles were

exposed. The problem was, however, that the joint fire plan could not commence

until daybreak, and the landings could not begin until the fire plan had been

completed. At Omaha this timetable left only 40 minutes for the execution of

the whole fire plan, including 25 minutes for the air element of the plan. The

longer term bombing operations mounted in support of the landings targeted the

larger coastal artillery batteries rather than the beach defences.

To deliver the largest possible quantity of ordnance on to the beaches

within this brief period, the aerial bombardment task was assigned to the heavy

bombers of the US Eighth Air Force. Bombing from the air was to be followed by

a naval bombardment, after which the first landing forces would hit the beach.

Their task was to capture the draws, while combat engineers cleared paths

through the obstacles and unblocked the exits. This would allow the following

waves of assault craft to be brought safely up to the top of the beach on the

rising tide; the troops and vehicles on-board would then advance inland through

the exits.

The factor that defeated the air support plan was the weather. D-Day was

planned for 5 June 1944 but postponed to the 6th on weather grounds, yet conditions

on the 6th were still far from perfect. The original air bombardment plan at

Omaha assumed clear conditions and visual bomb aiming. Specific targets – gun

batteries, strongpoints, and headquarters buildings – were even selected.

However, no such precision could be expected if there was extensive cloud

cover. The 8th Air Force practised attacking beaches through cloud using the

radar-based bombing aid H2X and were reasonably confident of their ability to

hit the target area so long as it showed up clearly on the H2X display.

Of necessity, enhanced measures were taken to ensure that the bombers

did not hit the landing force. In general, the bomb pattern from a formation of

heavy bombers tended to creep backwards from the target area, so crews were

directed to delay the release of their bombs, and the interval between the

bombing and the arrival of the first assault troops was also extended.

At dawn on 6 June, the bombers went in, flying at around 18,000ft. The

target area was covered by cloud, and they had to bomb using H2X. However, it

was found that the relatively featureless coastline was impossible to identify

clearly. In keeping with their orders, the bomb aimers delayed release to

ensure that they didn’t hit friendly forces, and the result was that they

bombed long. Hardly any bombs landed in the beach area, and most fell harmlessly in

the Normandy countryside.

The naval bombardment was barely more successful, partly because it was

too short, partly because it was not very accurate, and partly because the most

heavily armed ships were used against coastal batteries some distance from the

beach. Swimming tanks – Duplex Drive Shermans – were also supposed to provide

fire support, but they were launched too far from the beach, and most of them sunk

before reaching the shore. In summary, the air bombardment failed, the naval

bombardment failed, and hardly any tanks got safely ashore. So Omaha became, in

effect, an unsupported landing by infantry against extremely well prepared

defensive positions.

During the run-in, numerous landing craft went off course and beached

around the draws – the most heavily defended areas. Many were also halted by sandbars

well before the shore and offloaded the assault troops into water that was

anything from waist to neck-deep. When the ramps went down, the defenders

poured a devastating barrage of fire into the assault infantry as they tried to

struggle ashore. Within minutes, the tide-line at Omaha was transformed into a

state of chaos, confusion and carnage. Men tried to take cover in the water or

behind beach obstacles. Most of those who survived managed to cross the beach

flats and found a limited amount of shelter behind the shingle bank. Many of

them lost their officers or their units and jettisoned their equipment. None of

the draws were captured, and few of the beach obstacles were cleared.

|

| American troops seeking cover behind the beach obstacles during the morning assault on Omaha |

|

| Vehicles lined up along the shingle bank at high tide, unable to get off the beach |

An invasion force of 40,000 troops was now heading for Omaha on the

assumption that the beach had been captured and the exits opened. In fact, they

were all still closed. The second wave of landing craft suffered a fate similar

to the first, the troops who got ashore merely joining the others behind the

shingle bank. With a rising tide, congestion soon became a chronic problem, as

wave after wave of landing craft unloaded personnel, vehicles and equipment on to

a smaller and smaller area under continuous fire.

21 BD Sector

From the very outset, Allied planning for the Normandy operation

attached a high importance to the air defence of the lodgement area. The

experience of the Dieppe raid in 1942 suggested that the landings would

immediately be confronted by a strong and determined Luftwaffe response. By the

early spring of 1944, it was clear that the Luftwaffe’s daylight combat

capability was being severely degraded by the Allied strategic bombing

offensive and deliberate counter-air operations in Northern France, but this

merely increased the relative importance of night air defence. If the Germans

were no longer capable of presenting a significant air threat by day, they

could be expected to focus more of their efforts on strikes against the Allied

lodgement area under cover of darkness. For this reason, it would be essential

to establish radar warning and – especially – Ground-Control Intercept (GCI)

capabilities in Normandy as soon as the landings began.

In night air defence, GCI represented a critical capability. In the

daylight air battles over Southern England in 1940, the raid-reporting and

fighter-control functions of RAF Fighter Command had been entirely separate.

Intercepting fighter squadrons were vectored towards incoming raids, attacking

them once they were visually identified. However, by night, such tactics were

impractical for the simple reason that the fighter pilots could no longer spot

the raiders. Airborne radar offered one solution but lacked the necessary

range to be employed independently. GCI provided the solution by uniting raid

reporting and control at a single ground station. By plotting the course of

both the raider and the intercepting fighter, the ground GCI station could

direct the fighter to a position close enough to its intended target to allow

the final interception to be effected using Airborne Intercept (AI) radar.

For Normandy – drawing on the experience of Sicily – the Allies assigned

responsibility for air raid reporting and fighter control in the lodgement or

‘base’ area to 85 Group. The group reported directly to Leigh-Mallory’s Headquarters,

Allied Expeditionary Air Force (HQ AEAF), an arrangement that left the RAF’s

Second Tactical Air Force and the USAAF’s IX Army Air Force free to concentrate

on the provision of tactical air support for ground forces.

The 85 Group base defence plan for Operation Neptune assigned the

initial GCI task to three Landing Ships (Tank) (LSTs) specially fitted with

appropriate equipment. They were termed Fighter Direction Tenders and were to

operate off the landing beaches, while mobile GCI stations went ashore. The

first GCI units would subsequently be augmented by additional stations and

other warning capabilities, such as Chain Overseas Low (COL) and mobile Light

Warning Sets. Radar cover would thus be steadily increased across the base area

until a comprehensive radar screen had been established. It was planned to

deploy some 19 radar units by D+14.

The basic principles of this system were similar to those applied in the

United Kingdom. Following the landings, overall responsibility for warning and

control would be assumed by operations centres, to which all the deployed radar

units would report. Initially, however, 85 Group’s vanguard was to consist of

two Base Defence Sectors, elements of which would land on D-Day, one in the

British beachhead and one in the American. The first echelon of 21 BDS,

beaching at Omaha on 6 June, was 15082 GCI. Their primary equipment was the Air

Ministry Experimental Station (AMES) Type 15 GCI system, but they were also to

deploy with AMES Type 13 centimetric height-finding equipment, an AMES Type 14

centimetric plan-position station, an AMES Type 11 mobile radar and a

substantial communications element. Collectively, this equipment was referred to as AMES Type 25. Attached to 21 BDS was one company of a

British Army signals unit, 16 Air Formation Signals, and a number of their

personnel also landed at Omaha on D-Day. Their task was to establish the main

trunk telephone network for deployed RAF elements in Normandy and maintain an

overland delivery service, using jeeps and motorcycles.

|

| AMES Type 14 plan position |

|

| AMES Type 11 |

The officers and airmen selected to maintain and operate

GCI units in Normandy were first sent to RAF Renscombe Down, near Swanage in

Dorset, where they spent about a year training for their primary role.

Controllers and operators were subjected to a continuous programme of practice interceptions.

Later, personnel were also trained to carry out their duties under field

conditions. There were numerous exercises, including amphibious operations, and

commando training was provided at the Combined Operations School, HMS

Dundonald. The official monograph’s suggestion that unit personnel could all

‘be regarded as toughened fighting men as well as skilled technical tradesmen’

is, perhaps, something of an exaggeration. Nevertheless, they arrived in

Normandy equipped with Sten guns, rifles and pistols, knowing full well how to

use and maintain them.

Other training included driving instruction on all the

vehicles employed, and multiple practice ‘wet-shod’ landings – driving fully

waterproofed vehicles down the ramp of an LCT into an average depth of three and

a half feet of water and on to a beach.

Flight Sergeant Fulton Muir Adair later recalled this

period, when the personnel of GCI 15082 were ‘subjected to continuous and

rigorous training in wet landing procedures, combat exercises and anything else

that assorted Admirals, Generals and Air Marshals could concoct’. He personally

took courses in waterproofing vehicles, leading truck convoys, riding

motorcycles and even sailing small vessels. Aircraftsman Archie

Ratcliffe was an RAF driver with 16

Air Formations Signals. Ratcliffe describes travelling

to Inveraray, in Scotland, and finding himself in a training camp for Commando

units. ‘We were to be given intensive assault training and, believe me, they

really gave us the works … We then moved to Troon in Ayrshire, where we did

landing for two weeks, arriving off and on LCTs in various depths of water … We

had training with Sten guns and hand guns.’

|

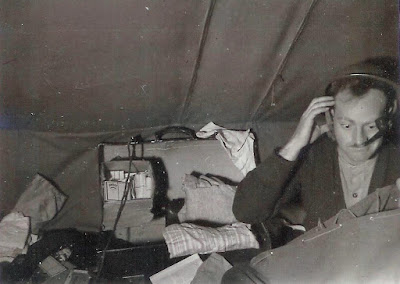

| On exercise under canvas: Muir Adair and two other members of 21 BDS |

The Americans were

friendly, helpful and efficient. More deadly serious, equipment was issued – an

American assault respirator, worn on the chest in a waterproof bag (destined to

be a lifesaver!); supplies to make us completely independent for forty-eight

hours (including three condoms!), and maps of the landing area showing fortifications

and machine-gun sites.

At the same time, elements of the unit were sent to

the RAF station at Old Sarum, Wiltshire, for another purpose. As

all their vehicles were to make wet-shod landings, each had to be completely

waterproofed so that it would run with its engine and gear-box submerged, and the

contents of the technical vehicles had to be waterproofed too. Waterproof

canvas bags were made to contain the equipment. Cracks in floors, window frames

and doors were all coated with grease and sealant. The Old Sarum operation is

another obscure but remarkable part of the D-Day story; ultimately, an army of

more than 1,000 fitters waterproofed some 25,000 invasion vehicles at the base.

Much of the surviving evidence seems to indicate that 21

BDS were well prepared for their assigned role in Normandy. However, there was

one particular oversight that was only remedied at the last moment. Until the final

week of May, they relied on RAF station medical facilities, and it was only at

the eleventh hour that a 21 BDS medical officer was appointed. Rugby

and Cambridge-educated and ‘very capable’, Flight Lieutenant

Richard Rycroft arrived on the 23rd. He had previously served as a

squadron medical officer and lacked the experience of other unit personnel of

‘life under canvas’. Moreover, as he was only transferred two weeks before

D-Day, there was no time for him to undergo the same rigorous amphibious

warfare training.

Rycroft found the unit desperately short of medical

supplies and promptly set about improving the situation. Initially, he was

expecting to deploy to France with one of the follow-up 21 BDS elements.

However, on 2 June, he was informed that the first echelon were concerned about their lack of medical support and required his services on D-Day. As he later recorded, ‘I was given an hour in which to make arrangements

and clear up my personal kit.’ He was assigned only the most limited

transportation space, allowing him to take:

1 regimental medical pannier

1 reserve medical pannier

1 blood transfusion box

1 surgical haversack

1 medical companion (1)

2 stretchers

Multiplied several times over, these provisions would

still have proved completely inadequate for the task that confronted Rycroft

four days later.

Isolated from the outside world at Sopley, 21 BDS personnel were

eventually briefed on the date of the Normandy operation, their landing craft, their

planned date of sailing and their probable deployed locations if the initial amphibious

landings went according to plan. They were scheduled to land mid-morning, after

the first assault waves had gone in. By this time, the tide would have covered

much of the beach, and the LCTs would therefore unload near the shingle bank. The

vehicles and personnel of 21 BDS would thus have the minimum of exposed ground

to cover. As we have seen, the expectation was that the beach would be securely

held; gaps would have been cleared through the beach obstacles, and the exits opened.

The relatively early landing reflected the importance attached to the establishment

of operational GCI ashore at the earliest possible moment.

According to their own after-action report, it was originally planned

that 21 BDS should land near the Colleville draw (numbered E-3 by the

Americans), in the more easterly sector of the beach. The reason for this is

unclear, as their objective for the day was to set up at a point some eight

miles west of Omaha at St Pierre du Mont, near Pointe du Hoc, so that they

could cover both American landing beaches. With the advantage of hindsight,

this can only be described as a hugely ambitious goal, which reflected not only

the RAF’s extensive preparations for rapid GCI deployment but also the extent

to which German opposition was underestimated.

D-Day

The first echelon of 21 BDS embarked in five LCTs on 2 June 1944 at

Portland, where they remained in harbour until the 4th. Early that morning,

the LCTs set sail for the French coast but then turned back when Neptune was

postponed because of the weather. They finally set out again at 0430 on the 5th

and reached the Normandy coast soon after daybreak on D-Day. The sea voyage was

completely without enemy interference, and enemy aircraft were conspicuous by

their absence, but strong winds made for a rough crossing and sea-sickness was

rife.

It was 1130 in the morning when 21 BDS first attempted to land. Their flotilla

moved towards the beach, the vehicles, all with their engines running, ready to

disembark when the ramps were lowered. However, as they closed on Omaha, it was

observed to be under heavy machine gun and artillery fire. In the words of the

official report, ‘it was obviously impracticable to land the convoy then.’ Two

American patrol boats, which were controlling the movement of landing craft

towards the beach, ordered them to withdraw.

Leading Aircraftsman John Cubitt was an RAF MT driver with 21 BDS, who

was just 20 years old on 6 June 1944. He recalled waking up early on the

morning of D-Day and witnessing the incredible sight of the invasion armada.

Every type of vessel from the largest

battleship to the small amphibious lorries called DUKWs. Destroyers and similar

vessels were dashing round ‘whoop-whooping’ on their sirens. They were using

loud hailers to issue instructions. As the scheduled time for our

disembarkation came and went and the destroyer activity increased with frenetic

urgency, we suspected there was something of a ‘hiccup’ in the arrangements. We

became aware that there was no movement on the beach.

Squadron Leader Norman Best, the technical officer responsible for the

GCI equipment, got close enough to the beach to see that it was ‘littered with

dead and wounded and the wrecked vehicles of our advance Beach Engineering

party.’ Archie Ratcliffe likewise recalled that ‘The scene was terrible … There

was heavy shelling and mortar fire, plus very heavy machine gun firing … The

commander of our LCT told us that we were to delay going ashore.’

Padre Geoffrey Harding was on an LCT with the first echelon’s commanding

officer, Wing Commander AM Anderson. As CO, Anderson had obviously expected to

lead 21 BDS onto the beach. However, on the morning of D-Day, he was suffering

from such chronic sea-sickness that he was in no fit state to do so. He asked

Harding to take his place, while he moved back to the fourth or fifth vehicle.

The padre readily accepted this commission but, after their landing was delayed,

Anderson’s original plan was reinstituted.

Flight Lieutenant Ned Hitchcock described setting off from the middle of

the invasion fleet under the direction of a patrol boat. As his LCT neared the

beach, it became clear that it was not yet in Allied hands. ‘The men ashore

were taking cover from enemy fire; there was a vehicle burning; as we watched,

an explosion blew a figure high in the air.’ Onboard the LCT was an American

observer, who possessed some experience of amphibious operations in the

Mediterranean. ‘He assessed the situation and concluded that the last thing

needed ashore at this stage was a collection of technicians armed with radar

aerials. Rather relieved, we turned seaward, presuming we could land next day.’

One fundamental problem that confronted the Allies after the initial

assault on Omaha was that command and control substantially broke down. Hardly

any radios survived the assault intact, and virtually the only reports reaching

General Omar Bradley’s headquarters ship, the USS Augusta, came from the

fragmentary accounts of landing craft coxswains returning to reload their

boats. A picture emerged of near-total disaster, and Bradley spent some time on

D-Day contemplating the abandonment of Omaha and the transfer of his invasion

forces to Gold and Utah. But withdrawal was not an option. It would have meant

abandoning the troops who had already gone ashore, as well as jeopardising the

entire Allied invasion plan by leaving a large gap in the beachhead. In truth,

there was very little that Bradley could do. The key command decisions had to be

taken further down the chain.

Inspection of the surviving gun emplacements on Omaha beach helps to

explain why the Americans experienced such extreme difficulty suppressing the

German defences on D-Day. Many of the German positions were designed to fire

diagonally across the beach. The diagonal view narrowed the gap between

targets, as compared with the perpendicular view, and (at Omaha) allowed the defenders to shoot directly behind the shingle bank, but this design also reduced

the casemate’s vulnerability. The embrasure is the weakest point of an

artillery casemate. If it faces outwards, the opponent’s fire can be directed

straight into it. The Germans reasoned that it made more sense to design

casemates to provide diagonal or ‘enfilading’ fire, and to hide and protect the embrasures with screening walls. Areas of the beach lying

beyond the arc of fire from one casemate would be covered by another, covered

by another, and so on. The guns in the eastern sector of Omaha mostly pointed

west, while those in the west mostly pointed east. There was a large

overlapping area between the Colleville and Les Moulins draws.

|

| German gun emplacements at Vierville, sited to shoot diagonally along Omaha beach |

After the naval bombardment lifted and the beach assault began, the

Allied destroyers patrolled the bay, their crews looking on as the first

assault waves went in. It soon became obvious that the landing had run into

ferocious opposition, but the destroyers at first suffered from the same lack

of hard information that so handicapped Bradley and his staff. No fire control

teams were functioning on the beach, and no targets were visible; any naval fire

into the landing area would run a severe risk of hitting friendly forces.

This situation prevailed for about two hours after the first troops went

ashore. From then on, individual destroyers began to close on the beach. The

closer they came, the more they could see of the enemy defences. By narrowing

the angle on the larger gun emplacements, they gained some visibility around

the screening walls and began shooting into the embrasures. Finally, at 0950,

all the destroyers in the bay were ordered to close on Omaha to the maximum

extent possible to engage the enemy defenders at close range. Despite the

absence of fire control from the beach, they played a crucial role in

suppressing German resistance.

|

| US naval bombardment of the D-1 draw at Vierville; the church spire did not survive D-Day |

Naval fire also gave a huge morale boost to the troops pinned down behind

the shingle bank. Beyond this, however, the realisation spread among them that

they had to move on from the bank and get off the beach. The original plan to

advance inland had focused on the draws, but they were clearly impregnable. The

only alternative was to go up the bluffs. The same basic conclusion was

gradually reached by officers and NCOs along the whole expanse of Omaha. Acting

on their own initiative, they changed the plan. Small teams formed up and began

fighting their way forward, marking paths through the minefields as they went.

When at last they reached the top of the bluffs, they fanned out to attack the

German defences around the draws. One by one, after a desperate struggle, the

resistance nests fell, but several beach exits remained firmly closed

throughout the afternoon.

From their LCTs, the members of 21 BDS watched and waited. The unit

report records how, ‘During this time, considerable shelling of the cliffs was

being done by the Navy to try and silence the shore batteries that were

established in the cliffs, continually shelling the beach. This went on right

up to the time of landing.’ Ned Hitchcock was one of those who looked on as the

naval guns pounded the shore. ‘We saw the Vierville clock tower destroyed (we

later learned it was suspected of housing German artillery observers). Mercifully,

we knew nothing of the desperate battle by the American infantry to gain a

foothold.’

All the published accounts of the landings at Omaha on D-Day agree that,

as the day wore on, the situation on the beach gradually improved. The German

gunfire slackened somewhat. The infantrymen who so gallantly fought their way

up the bluffs slowly pushed inland; the naval guns took a considerable toll on

the defenders. And yet, to judge from the subsequent first-hand accounts left

by members of 21 BDS, it seems possible that at least some of the German

gunners held fire merely because they were short of targets. Moreover, if the

threat from the gun positions along the beach was gradually being eliminated,

the Germans still possessed the means to bring heavy indirect fire to bear from

the batteries positioned inland.

By 1700, it was necessary to determine whether the 21 BDS landing would

proceed or be postponed until D+1. Tidal conditions were presumably a factor in

this decision. As the beach obstacles had not been cleared, landings with LCTs and

vehicles at higher tide levels would have been very dangerous. As the tide was

beginning to rise by 1700, further delay would have prevented 21 BDS from going

ashore. Yet there were many other units that did not adhere to their original

landing plans at Omaha on 6 June. Indeed, the various 21 BDS accounts maintain

that there were no further landings at Les Moulins on D-Day after they went

ashore, nor were there any on the morning of D+1.

It must therefore be assumed that they were ordered to land for

operational reasons – because of the vital importance attached to the

establishment of a night air defence capability in the lodgement area on D-Day.

Recalling the statement of an LCT coxswain, Muir Adair described how ‘the

Senior Royal Air Force Officer, “Officer Commanding Troops” ordered us in,’

although it is uncertain whether he was referring to the commanding officer of the

first echelon, the CO of 21 BDS or a more senior figure. Whoever was

responsible, it is clear that the third factor in the decision to land was the

notorious ‘fog of war’, manifested in this instance by the prevailing lack of

reliable information about the true situation on the beach. Finally –

critically – it was evidently not appreciated that the sand-bars that are a

feature of Omaha beach would prevent the LCTs from unloading close enough to

the tide line.

|

| Les Moulins at low tide; 21 BDS came ashore in this area, probably not long after the photograph was taken |

|

| A low-tide wet-shod landing just west of Les Moulins, showing submerged vehicles and troops struggling in deep water |

Members of the unit now saw that Omaha was still under heavy shell fire

from German artillery. ‘These guns had got the range of the beach and were

consistently shelling the American vehicles which were lined up … and unable to

get away as both exits were blocked.’

John Cubitt was driving the 21 BDS medical officer, Flight Lieutenant

Rycroft, and recalled seeing the ramp go down and a naval sub-lieutenant up to

his waist in water with a pole, testing the sea’s depth. ‘I was rather

surprised to see columns of water rise here and there as shells burst around

the ramp, not too near fortunately … I engaged four-wheel drive lowest gear and

stamped on the accelerator. The engine must not stall under water … I now had

the dubious honour of leading the column.’

On reaching the head of the beach I turned

right. My way up the sand was through the debris of war. Bodies in various

attitudes, radios, vehicles, rifles, equipment, tanks and half-tracks blown up

as they left the boats, and I was leading a column of ‘soft’ vehicles into this

carnage.

Cubitt and Rycroft were among the more fortunate 21 BDS members, in that

they succeeded in driving ashore. For most, the sandbars proved insurmountable

obstacles. The unit report continues: ‘Most of the craft were landed in about

4’3” of water so that immediately they struck a hole they were drowned.’ Such

was the experience of Padre Harding, who recorded coming off an LCT some

distance from the beach in fairly deep water, touching down and moving off. At

first, the engine kept going. Then, his vehicle disappeared into a shell hole

that had been covered by the rising tide. ‘I got out and found I could stand on

the bottom with the water just up to my chin, while my driver, who was rather

shorter than myself, took my hand and he swam and I waded ashore.’

|

| This object is either the AMES Type 13 or 14 belonging to 21 BDS; in the background is the eastern shoulder of the D-3 draw |

Archie Ratcliffe and the 16 Air Formation Signals personnel

apparently landed ahead of the other first echelon LCTs, and he made it to the

beach in his Crossley truck, only to be halted by a large crater – an old shell

hole or a hole left by a mine. He clambered out to find himself surrounded by

‘utter carnage’, abandoned the Crossley and took cover at the top of the beach

below the bluffs. A few other members of his unit dug in close by, but they

made several forays back into the open to retrieve the wounded. It was from

this location that Ratcliffe subsequently observed the RAF LCTs.

They were getting a hell of a beating … We

could see them trying to get off the beach with their vehicles, but [they] were

getting heavily mortared and machine gunned. We knew they were getting

casualties and losing vehicles.

In the end, the basic Type 15 GCI elements arrived safely on the beach – the

aerial transmitter, two diesels, a crane, communications support, a jeep and

four Crossleys and some other vehicles and equipment items were later salvaged. Nevertheless, the materiel losses were very high and included the AMES Type 11, 13 and 14. The Type 14 was later salvaged but could ‘only be regarded as a source of spares’.

Moreover, the vehicles on the beach quickly came under fire. Adair described the beach being ‘carefully and systematically plastered square by square by the Hun’. It seemed that the only shelter was offered by the Les Moulins draw, but, on approaching it, 21 BDS were confronted by a solid barrier of earth some five or six feet high. Their trucks and trailers were lined up right in front of the draw along with such American vehicles as had come ashore with them, but there was no way off the beach.

Inevitably, the relentless shelling took its toll. According to Firby,

the Germans ‘obviously could see what they were shelling as they hit many

trucks and troop concentrations.’ If they no longer had gun positions on the beach, they still had observers in contact with the inland artillery. Wing Commander Anderson, the Commanding

Officer, was shot in the arm and apparently played little further part in the

unfolding events. His deputy, Squadron Leader Frederick Trollope, took over.

Subsequently awarded the Military Cross, his citation reads:

His courage and devotion to duty in

organising the many parties of his unit on the beach, which was under intense

fire, and arranging the safe conduct of his men and vehicles, as well as

organising the evacuation of the wounded, were of a high order. In addition to

this work, Squadron Leader Trollope carried out his nominal duties throughout

the night and was mainly responsible for the successful operation of his unit

under great difficulties. All his duties involved continual movement over the

beaches and reconnaissance into enemy territory under fire. He displayed great

leadership and courage.

John Cubitt described seeing one of the 21 BDS airmen ‘lying on his face, his toes beating an agonised tattoo in the sand. An American spoke to Cubitt about the situation before moving away and sheltering by a truck. ‘Shortly afterward, I saw him slide slowly to the ground, his head bleeding on the wheel rim. He was dead.’ Further down the line, Cubitt saw Squadron Leader Victor Harrison with his foot blown off. He was being assisted by Flight Lieutenant Douglas Highfield, who then heard another incoming shell and threw himself on top of the wounded man. He was killed by the explosion.

Highfield came from Marple in Cheshire. He gained his pilot’s wings at the end of 1941 and was posted as a Flying Officer to 243 Squadron (Spitfires) in the following year. However, in August, he sustained a back injury that effectively removed him from the cockpit, and the squadron deployed to North Africa in November without him. He began the GCI Controller course in June 1943 and qualified in July; at the beginning of 1944, he was promoted to the rank of Flight Lieutenant and his posting to 21 BDS followed in March. The record states that he became a controller in 15081 GCI, so it must be assumed that he was transferred to 15082 at some stage between March and June. Highfield was the only 21 BDS officer to lose his life on Omaha beach on D-Day; he was just 22 years old.

Adair meanwhile stumbled on the body of one of his young radar operators who had lost an entire arm. Further west, he saw a bulldozer pushing wreckage aside to clear an exit, but then the driver was hit by enemy fire and tumbled off. ‘Another combat engineer climbed up, moved the bulldozer a few feet, and also took a hit. The bulldozer stopped.’

Like so many others, Bill Firby ran for the shingle bank. He saw many

American troops lying along the shingle, and called out to them asking what was

going on. There was no response. He called out again to no effect. Finally, he

crossed the last few yards of sand and reached the bank; it was only then that

he realised they were all dead.

The official report records that several 21 BDS vehicles were destroyed by

German shellfire. ‘This beach was more or less deserted except for the fact

that there were American wounded who had been lying about since the first

assault.’ Such was the situation that confronted Flight Lieutenant Rycroft and

his orderly, LAC John Reid. Rycroft described graphically how little protection

was truly afforded by Omaha’s shingle bank, where the majority of casualties

were incurred by men lying down or dug into shallow foxholes. The American

troops who had been wounded in the early morning assault had only received

elementary first aid, and some, after twelve hours in the open, were severely

shocked. Although slightly wounded himself, Rycroft set to work. ‘Their

dressings were checked and measures taken to keep them warm,’ but no American

medical units could be found.

|

| Destroyed Crossley and Austin trucks of 21 BDS on Omaha |

|

| Troops in foxholes behind the shingle bank |

However, Harding’s chief recollection was that ‘it came to me very strongly, indeed, almost as though a voice spoke in my ear, that we must get off that beach at all costs and take refuge under the shadow of the cliffs.’ According to Cubitt, Harding ‘saw that there was a road out blocked by a bank of shingle … Somewhere or other he found an armoured bulldozer and got the driver to doze away the bank.’ This may perhaps have been the same vehicle that Adair had previously observed. Best’s recollection was that the bulldozer ‘bit into our earth barrier as nonchalantly as only a bulldozer can, and in a matter of minutes we were free and on the move.’

|

| A bulldozer in action at high tide at the D-3 draw; despite the Herculean efforts of the combat engineers, the exits remained closed until the evening of D-Day |

Harding recalled waving 21 BDS forwards. ‘Somehow, we got off the beach,

and got our wounded off too.’ Ratcliffe remembered how the padre moved them off

the beach to a concentration area, and Firby described him calling out to them,

‘This way boys,’ and guiding them to relative safety, through the gap and the

barbed wire behind it. He was ‘amazingly calm and assured’.

The official report then records how 21 BDS moved up to Les Moulins. The

wounded presented the greatest challenge. A radio van emptied of equipment provided

a makeshift ambulance that carried thirty of them up to the hamlet in relays.

There, they were laid out in gardens or beside the road. Thirty more were

placed in a German artillery position about four feet deep and affording

protection from anything except a direct hit.

Together with Reid and Harding, Rycroft spent the hours of darkness moving from one wounded man to the next, adjusting bandages and applying dressings to wounds that had not been discovered in the early hours of the landing. He expected many of his patients to die but actually lost just three, and he would later express amazement at ‘the number of patients who survived after severe wounds, long periods in the open under very noisy and terrifying conditions, and with only elementary first aid and anti-shock measures.’

Together with Reid and Harding, Rycroft spent the hours of darkness moving from one wounded man to the next, adjusting bandages and applying dressings to wounds that had not been discovered in the early hours of the landing. He expected many of his patients to die but actually lost just three, and he would later express amazement at ‘the number of patients who survived after severe wounds, long periods in the open under very noisy and terrifying conditions, and with only elementary first aid and anti-shock measures.’

His limited medical supplies were soon exhausted, but a considerable

amount of American kit was recovered, and the Americans also carried far better

personal first aid packs than the British. According to Harding, they found an

American truck full of medical stores that had got stranded in a ditch: ‘We got

a lot of valuable stuff for the use of our doctor.’ The rest of the unit spent

the night lying on the edge of the road at the entrance to the hamlet, where

in most places there was a low wall that supplied at least some shelter from

periodic German artillery fire.

Many members of 21 BDS would have spent at least some time that night

contemplating the fact that they had been unable to fulfil their primary

mission on the night of 6 June – for eminently understandable reasons. It is

thus not surprising that the official report records the Luftwaffe’s minimal

and insignificant appearance in the form of six aircraft, believed to be Ju

88s, which dropped just two bombs on the beach and lost one of their number to

naval anti-aircraft fire in the process. Ratcliffe witnessed the raid and

recorded that the noise was incredible, ‘not only from Jerry but from all the

halftracks, machine guns and anti-aircraft guns that the Yanks had got ashore.

All the boats at sea were joining in as well. The amount of shrapnel that was

falling was unbelievable. It just showered down.’

Such was the experience of most 21 BDS personnel on the afternoon and

evening of 6 June 1944. Inevitably, however, there were individuals who became

separated from the unit, and one of these was Muir Adair. When he reached the

shingle bank, Adair could find no other unit personnel – only some American Rangers and a few sailors. Inspecting them, he noted that there were no

officers or NCOs, and he was told that rank insignia had been removed on-board

ship to reduce the threat from German snipers. ‘No one had told me about this

rather disturbing problem,’ he recalled later, ‘and so, with all my stripes and

golden crowns shining out for all to see, and whether I liked it or not, I was

apparently in charge.’ Under increasingly heavy fire – and like so many other

NCOs who took charge at Omaha on D-Day – he decided to get off the beach.

I jumped to my feet,

grabbed a carbine lying nearby (my Sten gun was lost with the truck), shouted

‘Let’s get out of here’, scrambled across the loose shingle, over the

embankment, across some grass, and tumbled into a trench that ran parallel to

the beach, my rag-tag group of lost souls following close behind.

After a few minutes, they climbed out of the trench

and zig-zagged across gently rising terrain until they reached another, firing

indiscriminately at anything ahead of them and driving out several German

soldiers. Next, under fire, they moved on to a third trench, where they found

more Rangers under the command of a lieutenant. Four of Adair’s motley

assortment of troops had fallen, but he had somehow acquired a medic and a

naval petty officer. ‘As it was now quite dark and we apparently had no place

to go anyhow, the lieutenant suggested that we take a breather and hunker down for

the night.’

D-Day was at an end, but the chaos of the Omaha landings would take several days to iron out. Fortunately for 21 BDS, elements of the US 116th division had made considerably more progress in the adjacent - so-called ‘Easy’ - sector of the beach by attacking up the bluffs. Subsequently, they advanced across open fields towards St Laurent. During the afternoon, engineers opened the E-1 draw, and vehicles began to move inland. By nightfall, the Americans were in firm control of the area between E-1 and D-3.

D-Day was at an end, but the chaos of the Omaha landings would take several days to iron out. Fortunately for 21 BDS, elements of the US 116th division had made considerably more progress in the adjacent - so-called ‘Easy’ - sector of the beach by attacking up the bluffs. Subsequently, they advanced across open fields towards St Laurent. During the afternoon, engineers opened the E-1 draw, and vehicles began to move inland. By nightfall, the Americans were in firm control of the area between E-1 and D-3.

D+1

Daybreak on 7 June brought further sniping and more

casualties, fortunately none of them serious. Trollope decided to reconnoitre

forward, partly to find more cover and partly to move 21 BDS off the road,

where they would be blocking vehicles arriving from the beach. However, he

subsequently decided against any relocation after one of his subordinates,

Flight Lieutenant Effenberger, reported heavy fire between Les Moulins and the

next village – St Laurent.

Their difficulties were exacerbated by a further problem that was all

too common on both sides during the Normandy campaign – combat identification.

At some stage before D-Day, in Adair’s words, ‘some obscure officer of field

rank, at an equally obscure HQ somewhere in never-never land … had issued an

order that we were to go ashore in Air Force blues. In Combined Ops we wore

khaki but in a holding camp, just before “D-Day”, we were ordered to exchange

our uniforms for blues.’ In a combat environment, worn, dirty or dust-covered, RAF blue quickly assumed an appearance close to German field grey,

‘particularly in the eyes of American Rangers, who had never previously seen an

Air Force type.’ It soon became clear that some of the small-arms fire being

directed towards 21 BDS came from the US Army. After a short time, most members

of the unit were re-clothed in American uniforms.

By mid-morning, with German artillery again bombarding the beach, Trollope

decided he could delay no longer. After a further reconnaissance, 21 BDS moved

about three-quarters of a mile inland and pulled into a field. The sniping

continued, but no one was hit. Finally, at about 2 PM, they were approached by

an American intelligence officer from the 49th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Brigade.

On the orders of his commanding officer, Brigadier General EW Timberlake, he

advised them to move to Transit Area 2, above the eastern slope of the draw. In

the words of the 21 BDS report, ‘This was the first official contact of any

sort that had been made with the Americans since landing.’

The unit relocated almost immediately, heading through St Laurent, where a fire-fight was still in progress, and doubling back east into the fields overlooking the beach. The transit area was crowded and noisy owing to the continuing artillery duel between the Germans and the naval vessels offshore, but they managed to find room to dig foxholes where they could sleep.

Rycroft had meanwhile toiled throughout the night to provide medical aid

to the wounded under the worst possible working conditions. Early on the

morning of 7 June, he went off in search of water and stumbled on three US

medical orderlies in a trench. ‘They had apparently left their first aid post

in the village during the previous evening, discretion being the better part of

valour.’ They now emerged and worked with their British counterparts throughout

the morning, giving plasma transfusions to some twelve selected cases while

Rycroft attended to sixteen American soldiers who had been found sheltering

behind a wall.

The unit relocated almost immediately, heading through St Laurent, where a fire-fight was still in progress, and doubling back east into the fields overlooking the beach. The transit area was crowded and noisy owing to the continuing artillery duel between the Germans and the naval vessels offshore, but they managed to find room to dig foxholes where they could sleep.

|

| US troops advanced up the bluffs between D-3 and E-1 before pushing inland towards St Laurent; Transit Area 2 was established in the fields to the west, overlooking the beach |

|

| Although resistance around Les Moulins continued, the American advance cut off the Germans in the beach area and shielded units like 21 BDS from potential counter-attacks from St Laurent |

At midday, several US medical officers arrived and informed Rycroft that

a clearing hospital had been established further down the beach. They

had been entirely ignorant of the situation in the Dog Red sector and were

apparently surprised by the number of casualties. During the afternoon, the

wounded were moved off to the hospital, using such vehicles as could be pressed

into service. All the serious cases were evacuated back to England that night. According to Rycroft’s MC citation, he tended to some 75 US casualties on 6 and 7 June as well as the 21 BDS wounded.

Labouring with no less determination throughout this period was Squadron

Leader Norman Best. Together with the other unit technical officers, he is said

to have ‘worked unceasingly, salvaging equipment of all sorts from the beaches,

ranging from vehicles down to small items of serviceable equipment from

derelict vehicles.’ Best himself described how, after a few hours’ sleep, he

led his men back to the beach despite the continued shelling and sniping, and

‘did a bit of salvaging and with the aid of our friend the bulldozer managed to

pull out two submerged diesel vehicles of the Type 11.’

One of ours had been hit – indeed, all our

vehicles had been more or less damaged on the beach, and standby diesels seemed

very desirable additions to our convoy. We also salvaged the Type 14 aerial

vehicle, which had stuck in the sands and suffered from sea water damage.

That evening, Trollope discussed the situation with Timberlake, who allegedly ‘had the radar outlook’ and wanted functional GCI protection as soon as possible. Best advised that they could establish a basic capability if a suitable site could be found, and the general therefore directed them to set up their equipment in an adjacent field overlooking the beach. They occupied this new position on the afternoon of 8 June and declared the AMES Type 15 operational on the 9th. It was, however, ‘in a parlous state and ... riddled with holes in the transmitter, receiver and aerial system’. The 21 BDS signals equipment was so seriously depleted that they were at first entirely dependent on a ground-to-air VHF channel for reporting and other surface-to-surface communication.

Throughout this period, the military situation was extremely precarious,

and the beachhead was no more than two or three miles deep. However, during the

9th, there was a marked improvement. German resistance collapsed in the

immediate area and US forces pushed inland. Effective command and control was

gradually established at Omaha, and it was against this background that a

signal arrived at the end of the afternoon ordering 21 BDS to pack up and deploy

to their planned site, which was now in American hands. Leaving only their Wing

Operations element behind in anticipation of the arrival of the second 21 BDS

echelon, they moved successfully on the 10th and set up their equipment in a

matter of hours to provide GCI for Allied night-fighters over the American

sector of the lodgement area for the first time since D-Day. That night, they

claimed one enemy aircraft destroyed and one damaged.

The second echelon of 21 BDS landed at Omaha soon afterwards, while the

third came ashore at Utah Beach on the 23rd. The drowned and destroyed

equipment abandoned on D-Day was promptly replaced. Indeed, the official

monograph states that ‘meticulous care had been taken … over the provision of

adequate reserves of technical vehicles and equipment for the speedy

replacement of losses … The radio technical vehicles were waiting, fully

waterproofed, to be called forward and only required shipping across the

Channel to make good the losses experienced in this disastrous landing.’

Conclusion

The first echelon of 21 BDS – including the 16 Air Formation Signals

element – lost one officer and nine ORs killed at Omaha on 6 June 1944. Apart

from the single officer, Flight Lieutenant Highfield, four of the ORs were RAF

and five were Army. Another RAF aircraftsman subsequently died from his wounds.

Five officers and 31 ORs were wounded. Apart from Anderson and Harrison, and an

RAF pilot officer, the wounded officers were Captain Rowley, Royal Artillery,

and a US liaison officer, Lieutenant Barnes. Overall, the first echelon’s

casualty rate was 25 per cent – much higher than expected.

For their heroism, leadership and devotion to duty during the 21 BDS landing, Trollope, Best, Harding and Rycroft were all awarded Military Crosses. It is believed that this is the only occasion in history when four RAF service personnel from one unit have been awarded MCs on the basis of their participation in a single action. Eckersall and Reid both received Military Medals. Regrettably, it has not been possible to establish whether any equivalent awards were bestowed on any of the Army contingent.

For their heroism, leadership and devotion to duty during the 21 BDS landing, Trollope, Best, Harding and Rycroft were all awarded Military Crosses. It is believed that this is the only occasion in history when four RAF service personnel from one unit have been awarded MCs on the basis of their participation in a single action. Eckersall and Reid both received Military Medals. Regrettably, it has not been possible to establish whether any equivalent awards were bestowed on any of the Army contingent.

Although Muir Adair courageously led an assortment of American

servicemen off the beach while under fire, he was not among the medals, possibly

because the action was not witnessed by any other 21 BDS personnel, but he was

later awarded the Croix de Guerre. More surprising, perhaps, is that

Highfield’s supreme act of self-sacrifice was not posthumously recognised in

any way.

There were certain very obvious flaws in the 21 BDS plan, notably in its belated and inadequate medical support provisions and in the higher command decision that the unit should wear a uniform that could be mistaken for German field grey. Nevertheless, in all probability, if they had beached at Omaha on D+1 or 2, the first echelon would have come ashore without any casualties and with their vehicles and equipment substantially intact.

Any concise explanation for the disaster that befell this unit on 6 June 1944 must focus primarily on the related issues of command, control, communications and intelligence. Effective command decisions must be informed by intelligence, which is invariably relayed by functional communications. At Omaha on D-Day, the debacle on the beach was enough to reduce shore to ship communication to minimal levels, and commanders were thus denied the intelligence they needed to make rational decisions that reflected the true situation on land. They also lacked an adequate understanding of the low-tide beach topography. And so, on the basis that 21 BDS might establish a functional GCI capability on the evening of D-Day, they were committed to an unplanned low-tide landing on to a beach that was under heavy fire and from which there could be no forward movement in conventional wheeled vehicles, as the exits were all blocked.

There were certain very obvious flaws in the 21 BDS plan, notably in its belated and inadequate medical support provisions and in the higher command decision that the unit should wear a uniform that could be mistaken for German field grey. Nevertheless, in all probability, if they had beached at Omaha on D+1 or 2, the first echelon would have come ashore without any casualties and with their vehicles and equipment substantially intact.

Any concise explanation for the disaster that befell this unit on 6 June 1944 must focus primarily on the related issues of command, control, communications and intelligence. Effective command decisions must be informed by intelligence, which is invariably relayed by functional communications. At Omaha on D-Day, the debacle on the beach was enough to reduce shore to ship communication to minimal levels, and commanders were thus denied the intelligence they needed to make rational decisions that reflected the true situation on land. They also lacked an adequate understanding of the low-tide beach topography. And so, on the basis that 21 BDS might establish a functional GCI capability on the evening of D-Day, they were committed to an unplanned low-tide landing on to a beach that was under heavy fire and from which there could be no forward movement in conventional wheeled vehicles, as the exits were all blocked.

Once committed to the chaos and carnage of Omaha, the personnel of 21

BDS were confronted not by the challenge they had planned for or expected, but

by a desperate struggle to stay alive until the battle for the beach was won.

In this unenviable situation, we may surmise that their pre-D-Day commando

training was of paramount importance and that, without it, their casualties

would have been much higher. Their personnel went ashore with at least

some understanding of survival under fire and they were led by officers who soon grasped that they were all doomed if they remained behind the shingle bank. Indeed,

it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the arrival of a small and cohesive group

of officers who were prepared to take command decisions played a vital role in

opening the Les Moulins draw – a tactical action with a significance that

extended right across the Dog Red and (adjacent ) Easy Green sectors of Omaha.

To a great extent, the Allied victory in the Normandy campaign was based

on their overwhelming logistical superiority. There were numerous occasions

when seemingly heavy losses of vehicles and equipment were made good in a

matter of days – if not hours – from prepared reserves in the UK. Moreover, the

cross-channel reinforcement task was for the most part far quicker and easier

than the drawn-out overland resupply and reinforcement process that confronted

the Germans, which was complicated still further by the ever-present threat

from Allied air power. Hence, the 21 BDS story represents something of a

microcosm of the broader Allied experience. It is not known whether their

manpower losses caused any particular difficulties in the aftermath of the

D-Day landings, but their rapid re-equipment allowed them to recover much of

their operational capability within a week or so and to fulfil their intended

night-air defence role over American forces in the Allied lodgement area.

(1) Medical Companion: a standard medical officer’s case of treatments, dressings and basic equipment.

Sources

21 Base Defence Wing Operations Record Book TNA Air 26/40

Air Historical Branch, The Second

World War, 1939-1945, Royal Air Force: Signals Volume IV, Radar in Raid Reporting (Official monograph, 1950)

Air Historical Branch, The Second

World War, 1939-1945, Royal Air Force: Signals Volume V, Fighter Control and Interception (Official monograph,

1952)

Air Historical Branch, The

Liberation of North West Europe Volume III, The Landings in Normandy

(unpublished post-war official narrative).

SC Rexford-Welch (ed.), Medical

History of the Second World War: The Royal Air Force Medical Services Volume

III, Campaigns (HMSO, London, 1958).

Historical Division, US Army War Department, Omaha Beachhead (6 June-13 June 1944) (War Department Historical

Division, Washington, 1945).

Report on the Co-ordination and Control by FDT 217 in Operation "Overlord", by Squadron Leader WY Craig, 23 June 1944 (contained in Notes on the Planning and Preparation of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force for the Invasion of North West France in June 1944, Appendices to Chapters I-IV, AHB).

Report on the Co-ordination and Control by FDT 217 in Operation "Overlord", by Squadron Leader WY Craig, 23 June 1944 (contained in Notes on the Planning and Preparation of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force for the Invasion of North West France in June 1944, Appendices to Chapters I-IV, AHB).

RAF Medal Award and Citation Lists, Air Historical Branch

RAF Casualty Lists, Air Historical Branch

%202.jpg)